Trending topics

Working at home during the pandemic

As the Coronavirus pandemic worsens around the globe, many people will find themselves isolated, working from home and could face some mental health challenges. In normal times, perhaps 10-20% of employees work from home at least some of the time, but in these changed times many more are teleworking, many for the first time. Homeworking and teleworking can bring both opportunities and stress and a few ground rules can help minimise problems and maximise the positive for all concerned.

For employers ….

- A big increase in teleworking can bring technical problems, where IT systems are overloaded, which in turn creates problems for the teleworker

- Supervision can create problems, especially where employers are used to seeing their employees all of the time

- Scheduling of work may need to be more formalised, meetings with staff may be more difficult to arrange

- Changes to the business as a result of the pandemic need to be actively communicated

For employees ….

- Uncertainty about the future can lead to increased stress

- Managing the relationship between work and non-work time can be difficult for many

- Where there are others living in the employee’s home, managing relationships with family and others can be difficult

- The teleworker can suffer from loneliness and isolation, especially where they live alone

Back to the Future or a Brave New World?

The last time there was such a blurring between workplace and home and between working and non-working time was in medieval times. Is there is a danger that those times might be revisited for many new teleworkers? Or will the opportunity to create a new working relationship be realised? Making the best of teleworking arrangements involves the creation of new and flexible structures and ways of working.

For the teleworker, they should:

- Schedule and organise their working day to meet the needs of the workplace, their household and their personal needs

- Take regular breaks and meals

- Stay in touch with work colleagues and supervisors

- Offer support to co-workers where needed

- Clarify and define work tasks with their employers

For the employer, they should:

- Be clear and regular in their communications

- Ensure there is adequate technical resource available

- Schedule regular, short meetings to manage workflow

- Clarify expectations of employees

- Be flexible in their approach to what is a new situation for many

Prof. KARL KUHN: President and co-chair of the ENWHP

RICHARD WYNNE: ENWHP Board member and Director of Work Research Centre (Dublin)

The Collision of Two Pandemics: Obesity and COVID19

The pandemic of COVID‐19 is bringing public health to the forefront of the society. Lacking herd immunity and in the absence of effective vaccines or antiviral therapies, countries around the world are witnessing an unprecedented strain on their health systems and disruption of economies.

While most people with COVID‐19 develop no symptoms or have only mild illness, a significant number of patients develop severe disease that requires hospitalization and oxygen support, or even admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) and mechanical ventilation.

Older age and comorbid diseases have been reported as risk factors for severe illness and death. However, a growing body of research suggests that obesity is also a key risk factor, particularly for younger patients.

People of any age with severe obesity (a Body mass index of 40 or more) are considered to be at high risk of serious illness from COVID-19, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Persons with obesity are already at high risk for severe complications of COVID‐19, by virtue of the increased risk of chronic diseases that obesity drives, such as diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, obstructive sleep apnea, some cancers, etc. Furthermore, people with obesity usually have multiple comorbidities at the same time.

Patients with obesity usually already have various degrees of pulmonary dysfunction and lower oxygen levels. They already are at increased pulmonary risk, and when they get COVID-19, a mainly respiratory illness, they are more likely to have serious lung complications. Research shows that the need for invasive mechanical ventilation is significantly greater in people with obesity, independent of age, sex, diabetes and hypertension.

Another concerning aspect is that obesity is associated with a state of chronic inflammation which weakens a person’s immune system, making it more difficult to combat infections. We have learned much from influenza in patients with obesity and there will almost certainly be parallels to COVID‐19. During the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, obesity was recognized as an independent risk factor for complications from influenza, and it is likely that obesity shall be an independent risk factor for severe complications with COVID‐19 as well.

In addition, prior research has shown that persons with obesity have diminished protection from influenza vaccines. They tend to get sicker from the respiratory disease even if they've been immunized. In fact, researchers have found that as people gain excess weight, their metabolism changes and this shift make the immune system less effective at fighting off viruses. The condition of obesity seems to therefore impair the critical immune response needed to both deal with the virus infection and to mount a robust response to a vaccine.

Furthermore, persons with severe obesity who become ill and require intensive care, present unique challenges in patient management—more bariatric hospital beds, more challenging intubations, more difficult to obtain imaging diagnostic studies (there are weight limits on imaging machines), more difficulty in positioning and transportation by nursing staff. And like pregnant patients in ICUs, they may not do well when prone. In general health systems are already not well set up to manage patients with obesity and the current crisis will expose their limitations even more.

There will likely also be a psychological toll of the viral pandemic. Persons with obesity who are avoiding social contact are already stigmatized and are experiencing higher rates of depression. The current COVID-19 pandemic will likely deepen the negative psychological effects of social isolation for people with obesity.

This pandemic brings into focus the vulnerability of the millions of people living with obesity and other lifestyle-related chronic diseases.

As we’re understanding more and more that the obesity pandemic can have a great influence on the current COVID-19 pandemic, and likely on future viral pandemics, we need to understand that taking obesity seriously should be part of future control of global viral pandemics.

What are the initial conclusions we can draw from these facts? First and foremost, all nations must develop and preserve efficient national health systems based on principles such as: “prevention is key”, “investing in the training of the health force is a continuous effort”, “medical services should be part of a care continuum”, “the patient should be at the center of the whole system”, etc. Research performed amongst various health systems over the last 30 years is telling us the same simple truth: health systems, no matter how weak or how strong, cannot be and should not be left alone.

In each European country the health of the population is the final result of the work performed by complex health systems, with their own peculiarities and idiosyncrasies, systems which may, or may not be properly funded. These health systems are serviced by multidisciplinary teams providing their services at various levels (primary, secondary, tertiary care), and relying on infrastructure which, even in the best endowed nation, can always be improved. But in the end, achieving positive health outcomes in the fight against COVID-19 might depend on very simple measures. Some of these simple measures may include lifestyle changes, improving nutrition-related habits and increasing individual physical activity.

In the end “health promotion across all settings” remains an approach which should be assumed by all medical staff, at all levels, and across all healthcare services. Therefore, Workplace Health Promotion could become a powerful tool in the hands of managers of companies that are striving to improve the health of their employees and their resilience in tackling pandemics, both as a workforce and at the level of the individual. This will improve the productivity of the workforce and will contribute to the overall effort of the society.

IOANA HARATAU, MD: Attending Physician at John H. Stroger, Jr. Hospital of Cook County, Chicago (Illinois)

THEODOR HARATAU, MD, MBA: ENWHP Board member and Project Officer at European Commission

GIUSEPPE MASANOTTI, MD: ENWHP Board member and professor at the Faculty of Medicine (University of Perugia)

Approved and made available the Second edition of Good practice in Health Reporting guidelines

Prevention is an essential component of an effective health system. Whether targeted at individuals or populations, interventions aim to enhance health status and maintain a state of low risk for diseases, disorders or conditions, that is, to prevent their occurrence through programs of information, immunization, screening or monitoring. Over recent decades, there have been a number of public health success stories with increasing coverage of populations in terms of immunization and screening as well as achievements in reducing accidents and lowering smoking and drinking rates through specific policy measures. Public health challenges remain as obesity rates both among adults and children risk an explosion of related illnesses and conditions if left unchecked.

Health reporting provides information to politicians and the public about the health, illnesses, health risks and mortality of a spatially and temporally defined population. One of its main tasks is interpreting data from different data sources. As a steering instrument in health policy, health reporting acts as an empirical basis with which to make rationally justifiable policy decisions. Furthermore, it accompanies health policy processes and enables public participation. As such, it is embedded within a particular political discourse. Reporting systems at the local, state and national level are subject to the respective legal and political frameworks. This means that health reporting:

- Provides a description of the health of the population. It takes into account the unequal social and regional distribution of health risks and potentials for disease prevention, and demonstrates areas at the national, state and local level where action needs to be taken.

- Accounts for gender, migration and any other living conditions that influence the health of the population or selected population groups.

- Acts as a foundation for the cross-departmental planning of disease prevention, health promotion and care provision, and can be used to evaluate health policy measures.

- Involves the continuous collection of data about the health of a population and identifying possible changes in health at an early stage. Therefore, it can be used to make timely health policy decisions.

- Is not only aimed at experts and decision makers from politics and administration but also at the general public.

- Promotes the process of forming public opinion by providing information and enabling people to participate in drawing up health policy objectives.

- Supports the civil society concern of participation.

The boards of the German Society for Social Medicine and Prevention and the German Society for Epidemiology have approved the second edition of Good Practice in Health Reporting that complements Good Practice in Health Reporting complements Guidelines and Recommendations for Ensuring Good Epidemiological Practice and Good Practice in Secondary Data Analysis by providing additional, albeit central, recommendations for health reporting.

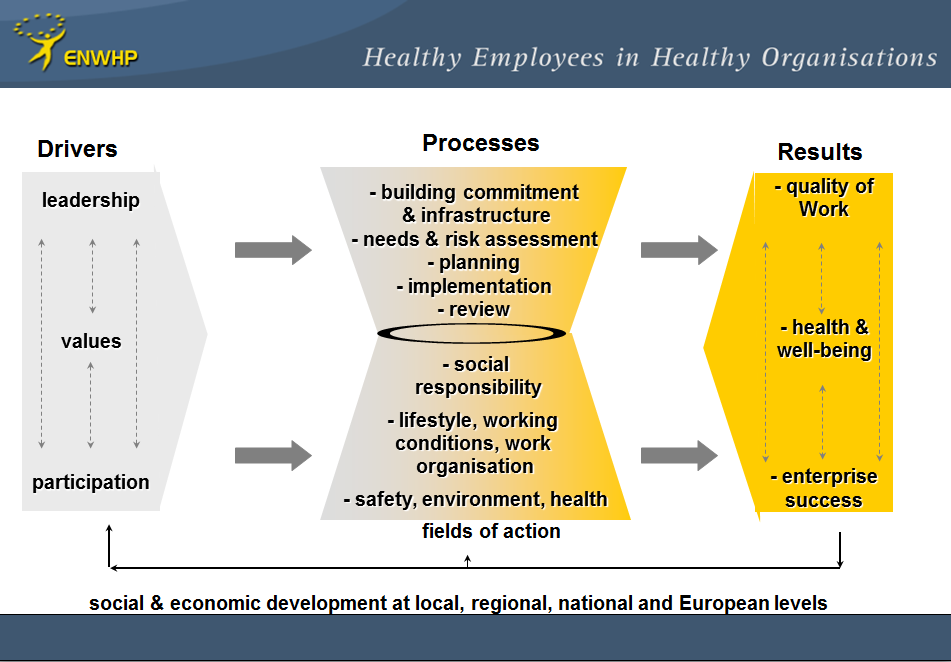

ENWHP approach to promoting workplace health

As a result of the good practice projects undergone by ENWHP since its foundation ENWHP approach to promoting workplace, healthENWHP has developed a general model of workplace health management which can be regarded as a general action model for the implementation of good workplace health practices at the enterprise level. This model is based on the assumption that it’s important to combine and integrate existing workplace health-related disciplines to improve effectiveness and to ensure compatibility to general trends in management thinking. The term “workplace health management” has been introduced in order to emphasise an enlarged focus on a comprehensive concept of workplace health by combining different professional disciplines and stakeholders.

ENWHP model identifies FOUR main elements:

Drivers

This element concerns the extent of integration of health-related aspects into the structure of an organization. Three aspects can be distinguished:

|

Values, ethics, theories and underlying beliefs (organizational culture) |

|

The way how health-related aspects are integrated into management practices (leadership). |

|

The way how the employees are involved (particularly with regards to health-relevant decision). |

Actions

Three levels of actions can be identified:

|

Measures in the field of occupational safety and health as well as environmental health comprising the statutory required measures. |

|

Lifestyle measures as well as measures aiming at improving working conditions. This category contains those measures that go beyond the legal requirements. |

|

Measures in the area of social responsibility. |

Processes

The element “Processes” describes an ideal phase model which applies to all fields of action mentioned above:

|

Building support and commitment. |

|

Developing an infrastructure. |

|

Assessing needs. |

|

Planning. |

|

Implementing. |

|

Evaluating and consolidating. |

Outcomes

This element contains THREE sectors:

|

Employee and customer satisfaction. |

|

Health outcomes. |

|

Business outcomes. |

ENWHP history and achievements: The beginnings

“Healthy employees in healthy organisations” – the ENWHP vision. Based on the Maastricht Treaty and the introduction of Paragraph 129 into the EU Treaty, the European Community developed in 1995 the Action for Health Promotion, Information, Education and Training Programme (COM(94)202 final). Within the framework of this programme, the Commission’s task was to organize the exchange of information and to support, encourage and coordinate health promotion activities.

As workplace was considered one of the most important areas of activity the Commission asked the Federal Institute for Occupational Health and Safety in Dortmund (BAuA) to act as a liaison office to:

| - develop an integrated action plan on health promotion at work in the European Community; |

| - develop a proposal for an information network to harness the resources available in the Member States; |

| - establish conditions under which an informal network for workplace health promotion could be created and to present a proposal on how to set up and run it. |

A concept of Workplace Health Promotion (WHP) had to be drawn up before BAuA was able to commence its work on 1st December 1995. More than 50 representatives from a variety of institutions of the Member States came to Dortmund the 21st June 1995 to report on the situation of WHP and they discussed objectives and main elements of an informal network. The final report (“Integrated Plan of Action for Workplace Health Promotion in the European Union”) concluded the preparatory work and the Liaison Office could begin working.

Nearly all of the then Member States expressed their interest in taking part in this new network and to set up a contact office in their own countries.

The first official meeting of the Network took place on 6 February 1996 in Luxembourg. It was clear from the beginning that there were great disparities between the participating countries, as well as considerable differences in the approach, methods, processes and issues, that influenced WHP policy. Even the term Workplace Health Promotion was virtually unknown in the northern European languages or did not mean the same thing to all members of the network.

In fact, the FIRST CHALLENGE was to agree on a common understanding of WHP and the FIRST ACHIEVEMENT was the Luxembourg Declaration, ratified in 1997, setting out for the first time, a Europe-wide, commonly agreed definition of WHP:

Photo credit: Beginnings by Andrea Parrish - Geyer on https://www.flickr.com/photos/tinytall/7259499574